Corn

Overview

Corn plays a central but carefully bounded role in the field system at Grey Barn Farm. It is grown primarily as a feed crop to support livestock across seasons, rather than as a standalone production enterprise. Decisions about when, where, and how corn is planted are shaped by field history, soil condition, weather patterns, and animal needs, with an emphasis on continuity rather than yield maximization.

Corn is not planted everywhere, every year. Its place in rotation varies by field and by season, and its use is considered in relation to what has come before and what will follow. In this way, corn is treated less as a destination and more as one phase in a longer sequence of land use and recovery.

Role Within the Livestock System

At this farm, corn exists to provide flexibility in feeding rather than to drive acreage decisions. Grain supports livestock through winter and periods when pasture growth is limited, helping stabilize rations across species and life stages. The amount grown is tied to on-farm need, storage capacity, and the condition of individual fields, not to external market signals.

Because livestock remain the organizing center of the operation, corn acreage expands or contracts as animal numbers and forage availability change. This keeps crop production responsive to actual use rather than fixed targets.

Field Selection and Timing

Not every field is suited to corn in every year. Field selection reflects soil structure, drainage behavior, prior crop history, and recent weather patterns. Fields that show signs of compaction, poor infiltration, or nutrient imbalance may be rested or placed into a different crop rather than pushed into corn production.

Timing is equally variable. Planting schedules adjust year to year based on soil temperature, moisture, and forecast conditions. Delays are treated as normal rather than as failures, and in some seasons the decision is made not to plant corn at all in a given field if conditions are unfavorable.

Rotation and Recovery

Corn is never treated as a continuous crop. Its place in rotation is deliberately temporary, followed by rest, forage, or other crops that allow soil structure and biological activity to rebalance. In some cases, this means leaving a field out of row crop production for one or more seasons.

Rest is considered part of the productive cycle. A field that recovers structure, improves water handling, and returns to corn later in better condition is regarded as more functional than one kept in constant use.

Soil Protection and Surface Management

Throughout the growing season, attention is given to protecting the soil surface. Residue from previous crops is left in place where possible, and unnecessary disturbance is avoided. Maintaining cover helps limit erosion, preserve moisture, and buffer soil from temperature extremes.

Field operations are timed to avoid working ground when it is too wet or vulnerable to damage. The visual appearance of a field is secondary to how it performs under rainfall and traffic.

Nutrient Inputs and Amendments

Nutrient management for corn is approached conservatively. Manure and lime are used where appropriate to support soil function and nutrient balance, informed by field history and soil testing rather than routine application schedules. Amendments are applied with attention to timing and conditions, rather than as blanket treatments.

Chemical inputs, including herbicides, are used infrequently and only when conditions justify their use in this system. They are considered one tool among many, not the foundation of field management.

Weather as a Governing Factor

Corn production is especially sensitive to weather, and management reflects that reality. Excess moisture, extended dry periods, heat, and wind all influence both planting decisions and crop performance. Rather than attempting to override these factors, management adjusts in response to them.

Some seasons favor corn; others do not. Accepting this variability reduces pressure to intervene unnecessarily and allows decisions to remain grounded in actual field conditions.

Harvest and Use

Harvest timing is guided by both crop condition and storage considerations. Decisions balance grain maturity, weather forecasts, and equipment access, with an emphasis on protecting both the crop and the field itself.

Once harvested, corn is incorporated into livestock feeding programs as part of a broader mix of forage and grain. Use varies by species and season, and adjustments are made as animal condition and pasture availability change.

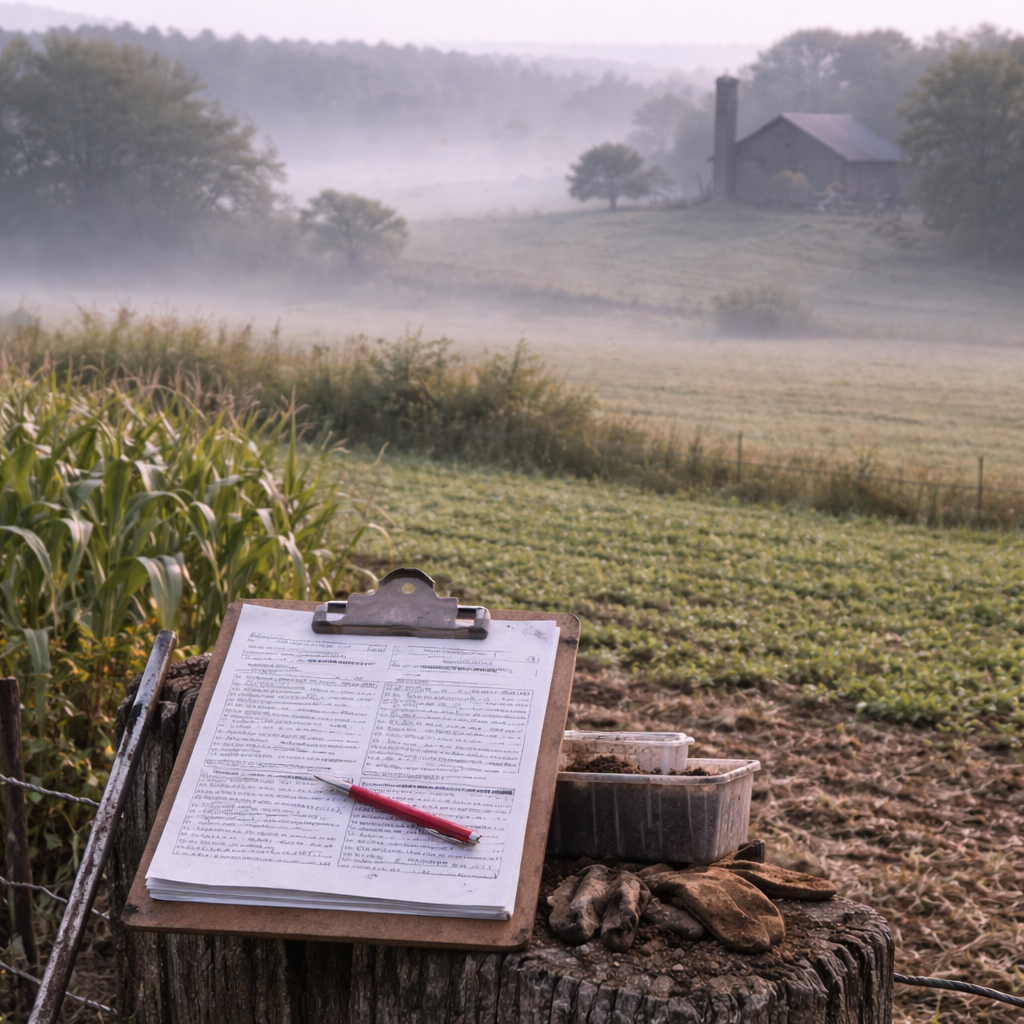

Record-Keeping and Field History

Corn fields are tracked alongside other crops and livestock in FarmBrite, with records that include planting dates, amendments, observations, weather conditions, and harvest outcomes. These records preserve context across years, allowing decisions to build on actual field experience rather than generalized guidance.

Over time, this accumulation of field-specific history informs whether corn remains a good fit for a particular parcel, or whether a different use would better serve long-term land function.

Corn Within a Long View

Corn at Grey Barn Farm is not managed for speed, scale, or maximum extraction. Its role is practical and bounded, shaped by what the land can sustain and what the livestock require. By allowing flexibility, rest, and adjustment, corn remains part of a system that prioritizes durability over short-term output.

In this context, success is measured less by yield than by whether fields remain responsive, resilient, and capable of supporting both crops and animals over time.